John Contreras, a distinguished engineer in Western Digital’s hard disk drive (HDD) CTO group, always knew he liked to build things, from electronic amplifiers and logic circuits to skateboard ramps. But he wouldn’t be the distinguished engineer he is today if not for influential high school math teachers and a fluke skateboarding accident resulting in losing a job. This succession of events led to a master’s level education at Stanford, dozens of published patents, and a surprise encounter in a tech museum in Paris.

An early affinity for tinkering

It’s hard to imagine that an inventor with more than 100 patents never envisioned embarking on a career in technology. “I had no aspirations to go to college. It just wasn’t on my roadmap,” said Contreras.

But Contreras was always drawn to building things. As a kid growing up in rural Texas, he had a subscription to Popular Electronics. The publication featured kits with a list of parts and instructions for readers to build things on their own. Contreras was hooked.

In high school, Contreras’s passion was mostly for his vocational courses, including metalworking and woodshop. However, one of his math teachers spotted his knack for numbers and wanted to nurture his talent. She encouraged him to take advanced placement calculus and petitioned for him to be enrolled.

Aside from that one advanced math class, “I wasn’t exactly on the fast track to college,” said Contreras. When he first applied to the University of Texas at Austin, he was rejected.

After high school, Contreras went to work in the fiberglass industry.

From pipes and halfpipes to Stanford’s hallways

“I was grinding large 10-foot pipes in the hot Texas summer sun. My co-workers all said, ‘you’ll get used to it!’” Contreras said. But he was let go after he could not work because of a skateboarding accident that broke his leg. He considers this experience to be a turning point; the moment that led him to find his way to Sam Houston State University, which he attended for a year, invigorated with a renewed sense of focus.

“When I was younger and building those circuit kits, I’d get those kits and some guidance, but it didn’t give you the math and theory behind it,” said Contreras. “That’s what I got from school: the math and science behind it, the details and intricacies that feed it.”

After a year of attending Sam Houston State with exceptional grades, he was accepted to the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied microwave and analog circuits engineering. Analog circuits came easily to him from his circuit-tinkering past, and he proceeded to attend Stanford University for his graduate degree. There he studied under several renowned professors, including Professor Emeritus Bernard Widrow, one of the fathers of neural networks.

At this point, he thought his passion was in signal processing. He did well but found himself seduced by control theory and robotics, which led to his master’s degree in mechanical engineering. His passion for building things remained a constant.

Contreras got his first tech job at IBM in the electronics packaging group. Wanting to get back into signal processing, he then took on a role at Phillips to work on new analog circuits using decision feedback equalization (DFE).

However, when Phillips decided to leave the HDD business, Contreras moved on to IBM Research-Almaden. There he worked under a mentor, Jack van Peppen, whom he considers his “Einstein” with expertise in circuits, magnetics, mathematics, and control theory.

IBM’s storage product and research divisions were purchased by Hitachi in 2003, which became HGST, and then Western Digital when it acquired HGST.

From the iPod to the data center

Contreras’ inventiveness and love of building things have earned him over 100 patents, spanning a range of technical areas from signal integrity and electronic packaging to circuit architectures and electromagnetic compatibility.

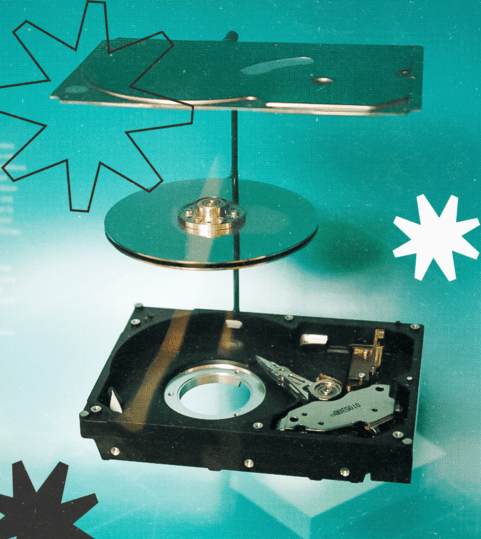

Among his favorite innovations was the 1” Microdrive developed by IBM and ultimately delivered by HGST, that went into the first iPods.

“That was exciting at the time – to see our Microdrive go out into handheld units back then,” said Contreras about the era before flash technology became ubiquitous in everything mobile, and as mobile technologies evolved, so did the embedded storage inside.

He developed several wave shaping innovations to address bandwidth issues in components’ packaging. Prior to Western Digital’s helium-sealed data center hard drives, there were more issues with suspensions and enclosures, where extrinsic electrical signals disrupted small readback data signals (ex., Wi-Fi and cell phone). To aid in the detective work in revealing these issues of radio-frequency (RF) susceptibility and emissions, robotic scanners with an end effector leveraging RF probes would peek into the emissions and identify culprits that caused signal interference.

As storage devices become more complex, so do their challenges. Today, Contreras leads an advanced-signal technology and circuits teams. The teams’ current investigations are centered on next-generation electronics for high-speed data transfers, signal integrity, and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). Innovations that will help Western Digital deliver the next generation of HDD and SSD storage products, pushing the boundaries on what’s possible.

With such a rich career, Contreras emphasized that it is important for him to serve as a mentor, sharing the knowledge and experiences he has gained with the next generation by mentoring engineers in his organization and through Western Digital’s We.Unidos (Hispanic & Latin Network), an inclusive employee resource group.

Taking risks

Contreras is humbled by his contributions knowing that it takes the whole team to generate ideas and execute them into products. Still, his contributions can be found far and wide, even in unexpected places.

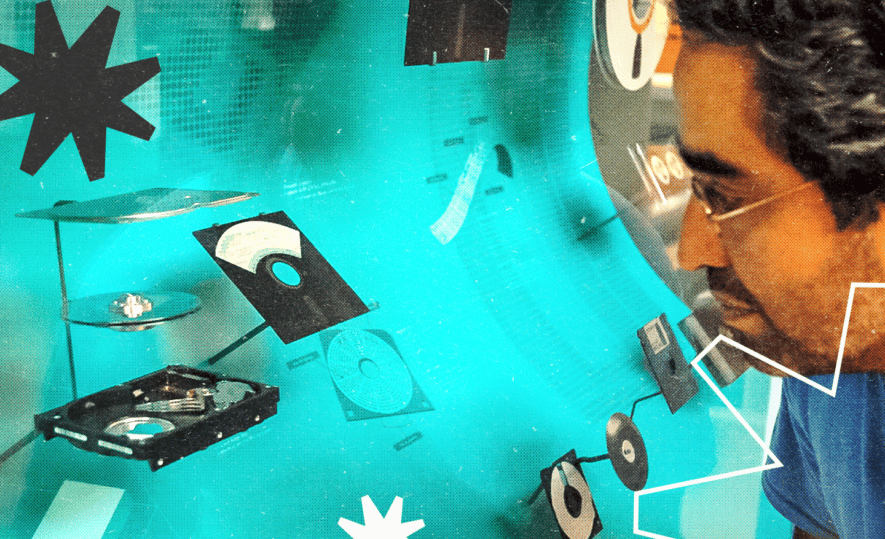

On a family trip to Paris in 2008, he and his son [then 16] were perusing exhibits in the Musee des Arts et Metiers Paris, a museum of technological innovation that houses over 2,400 inventions. While viewing the enormous Cray supercomputer display, they stumbled upon a smaller exhibit of hard disk drives showing the internals with the components that Contreras designed. His son asked: “Is this what you design, Dad?” Contreras had no idea his inventions for integrated circuits (IC) and the flex circuits, used on actuators in a hard drive, were a part of the museum’s display.

When it comes to breakthroughs, Contreras believes ideas are all around us to discover. He often goes hiking with his daughter, a biologist and artist who loves nature. “She sees things I don’t see: insects, bugs, little animals,” said Contreras. “But they’re there if you have that keen eye and perception to discover them.”

For him, that’s the approach to invention: looking at a problem in different ways and angles to reveal an idea to become an innovation.

“You have to have the background, a love for tinkering, and are willing to take risks,” he concludes. His teenage years taking risks on a skateboard have contributed to his ability to develop skills in new areas and push the envelope when developing new technologies.

“If you don’t open up to some risk, you don’t open up to innovation,” he said.