The Invention of the SD Card: When Tiny Storage Met Tech Giants

In 2014, at the National Medals of Science and National Medals of Technology and Innovation award ceremony, former President Barack Obama took a SanDisk SD card from his pocket and held it for the audience to see.

The 512GB card was a gift from SanDisk’s former CEO, Eli Harari, who was awarded a medal that day. It was a symbol of how flash storage made data ubiquitous in consumer electronics.

Nearly 10 years later, the SD card hasn’t lost its relevance. The tiny device is used in everything from gaming to industrial IoT. Its development started more than two decades ago in a small office in Tefen, Israel, during a time when Japan’s electronics giants were arm-wrestling to dominate the consumer market.

Flash back

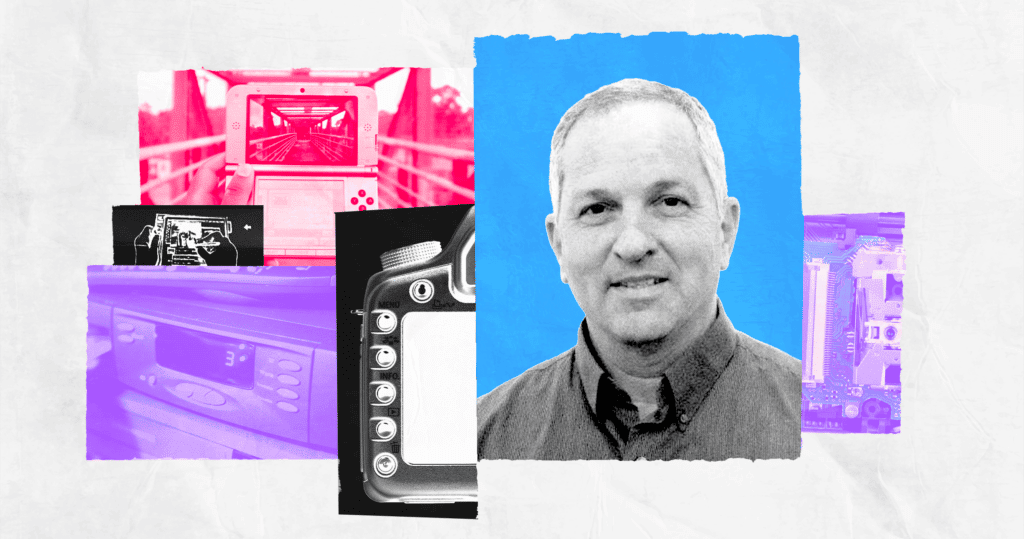

When Micky Holtzman, senior director of technology assessment at Western Digital, was asked to be the technical lead of SanDisk’s (later acquired by Western Digital) first office in Israel, he gave up a job managing 100 engineers to take a leap of faith in the future of flash memory.

It was 1996. Floppy disks were still sold by the billions. But flash was starting to carve its path with formats like CompactFlash, introduced by SanDisk two years prior.

Joining the four-man office, Holtzman was asked to work with Siemens, and then mobile giant Nokia to define a new memory card and storage standard: the MultiMediaCard (MMC).

“From an engineering perspective, what MMC and today’s memory cards do, is that they hide the complexity and uniqueness of flash behind a host interface that is trivial, clear, and simple,” said Holtzman. “From the outside, it’s just a memory device to which you can read and write to. But reading, writing, and erasing on the memory end is not simple at all. There is so much innovation needed to keep data reliable.”

The potential of postage stamp-sized storage was phenomenal. But MMC’s adoption was slow.

Nokia, which led the mobile phone revolution, had just introduced its 8000 series’ with the “slider” form factor (famously used in The Matrix in 1999). But the company, and industry, lagged in introducing products to support MMC.

By this time, Yosi Pinto, senior technologist at Western Digital, had joined the small SanDisk office in Tefen. Pinto, whose career path took him to telecommunications, had always aspired to be a chip designer, which was his major for his master’s degree. This was the job of his dreams and he left his senior R&D management position to join the start-up like environment.

Exhilarated, he quickly learned the ins and outs of the ASIC design (the chip that serves as the brains of the storage device) of MMC products.

The birth of the SD card

A year into Pinto’s job, a remarkable proposal came. Electronics giants Toshiba and Panasonic (then called Matsushita) asked the company to lead the design of a new memory card based on SanDisk’s knowledge in MMC but to develop it with a sturdier design, higher speeds, security features, and other improved capabilities.

Holtzman and Pinto flew to Sunnyvale for confidential meetings with Toshiba and Panasonic. “No one in the company even knew about these meetings,” said Pinto. “We weren’t allowed to say who we are meeting or why.”

In those days, Japan was the mecca of consumer electronics. Toshiba and Panasonic saw their competitor, Sony, developing a proprietary memory stick for its products. Teaming with SanDisk was an exquisite coopetition opportunity to gain ground.

“It was a crazy time,” said Pinto. “We would fly out to meetings in the Bay Area and return to Israel a day later to get back to work. We were this small company working with the largest names in the consumer world; the little guy making it happen.”

With Holtzman still involved with the advancement of MMC, Pinto led the technology innovation of the first SD card, focusing on the chip design of the card controller. He would be the principal editor of what would become the first SD specification.

Pinto, Holtzman, and several other former SanDisk engineers contributed many essential SD patents. Panasonic drove security requirements around digital rights and copyright protection, foreseeing the rise of MP3 players. And the two electronics giants used their heavyweight consumer experience to design a robust and easy-to-handle product.

“Toshiba and Panasonic would come to Israel in large numbers, always with these super thin high-tech laptops that we were so impressed by,” recalled Pinto.

When Pinto learned that a team of 20 engineers was waiting to work on the project in Japan, he joked that it was only him and a back-end engineer working on the project in the U.S. His Japanese counterparts offered to help.

“They said, ‘give us a room and teach us what we need to know,’” said Pinto, who then, for several weeks, became a manager of five new engineers and a significant language barrier to cross.

A versatile envelope

As Pinto worked on the chip design’s completion, he also taught the engineers from Japan the front-end blocks of the SD interface, allowing Panasonic and Toshiba to build their own controllers.

Just one year after commencing, the first SD card samples supporting a whopping 8 and 16 megabytes (MB) were ready. Soon after, SD cards supporting 32MB and 64MB were introduced to the market by all the three companies.

“Toshiba and Panasonic promised that whatever card we created, they will immediately release products to support it, and that’s exactly what happened,” said Pinto.

“It changed the world,” said Holtzman. “We brought a new product to the market that was an enabler. It made new applications possible that weren’t possible before. [Small] digital cameras wouldn’t exist. Smartphones wouldn’t exist,” said Holtzman and pointed to the gadgets in his office the SD card helped birth.

While many companies followed in adopting the SD card, others commenced what would become a decades-long memory card format war. Formats such as Fuji and Olympus’s xD Picture Card, Intel’s Miniature Card, and even Sony’s Memory Stick rose and fell as the SD card gained popularity.

It wasn’t just chance that the SD card prevailed. In 2000, SanDisk, Toshiba, and Panasonic established the SD Association (SDA) to set memory card standards that could simplify consumer electronics. The association, which has grown to about 800-member companies, helped the SD card adopt new features driven by applications and consumer demands.

The specifications are far too long to list but include everything from I/O features like Wi-Fi and Bluetooth through security capabilities to the never-ending increase of capacity and bus speeds made possible by the latest SD Express cards (boasting the addition of the PCIe®/NVMe™ interface).

The SD card proved to be a versatile envelope.

“A lot of things rose, fell, or completely changed in the last two decades, but this product managed to survive,” said Pinto. Pinto has been elected as SD Association chairman of the board for nearly a decade and is still closely involved with SD card developments at Western Digital.

By now, hundreds of the company’s engineers are working to push the boundaries of the small storage device, including delivering the world’s first 1TB microSD card and higher capacities to be soon introduced.

Changing the world

With nearly 100 patents to his name, Pinto sees the SD card’s impact as much more than technology alone. “The SD card wasn’t about creating cutting-edge technology for outer space or some complex chip hidden in networking,” he said. “It was bringing something new to the market that eventually everyone started to use.”

Pinto first saw SD Cards at airports. Then, he ran into them at various stores and, eventually, even in the little photography shop in the small town where he lived.

“Changing the world is easy to say, but it is difficult to do,” said Eli Harari on the day he received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation. “When you make a technology very cost-effective, very affordable, and give that benefit to billions of consumers, [it] democratizes information, knowledge. Information is knowledge. It gives power to the people.”